How the 1940s demonstrated that style is a statement of strength

and fashion can be a form of defiance.

A cold February Saturday morning found me, once again, in the town of Chertsey, UK making a return visit to the Olive Matthews collection.

Starting when she was a child, Olive Matthews was a prolific collector of men’s, women’s and children’s fashionable clothes from c1700 to the present day. She had an exceptional eye and was going to the Caledonian Road Market in London to buy ‘vintage’ long before it became the trend it is now. She valued the beautiful things she saw and wanted to preserve them. Many of the pieces in her collection are considered to be of National importance and she was frequently invited to the Costume Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum which helped her expand her knowledge about her collection.

The Chertsey Museum is small and intimate and does not have the luxury of space to display the whole collection permanently, so every September the collection display is changed, making it even more of a treat to see.

You can read more about Olive Matthews here.

Fashion from the 1940’s

The theme for the 2023–24 collection is fashion from the 1940s, a time when not only food but also clothing was rationed. We step into the world of the 1940s, a time when resilience was woven into every stitch of fabric, and style was more than just a trend — it was a symbol of strength and solidarity. In the chaos of World War II, when rationing wasn’t just a word but a way of life, clothing became a statement of defiance, a declaration that even in the face of adversity, we would not be defeated.

The 1940s was a tumultuous decade, characterised, in the first instance, by the Second World War (1939–1945). Everyone was involved, except the very young and the very old. It was a conflict where British civilians experienced the front line in the form of bombing raids. The physical and mental toll was enormous and the government of the day realised that ordinary people on the Home Front would be required to be wholeheartedly involved and be required to have a united and democratic approach.

Resilience, pride and dignity

Clothing became a crucial tool in this fight for morale. In a time when resources were scarce, and every thread counted, being “well turned out” was more than just a fashion statement — it was a statement of resilience, a refusal to let circumstances dictate the sense of dignity. It was a way of keeping their heads held high and maintaining pride whilst demonstrating they would not be defeated. Clothing played a key role in boosting morale and maintaining normality.

The Government were aware that due to the restriction of resources, scarcity meant the risk of panic buying and price inflation and knew they would have to impose rationing if there was to be a fair system for all. Therefore, the State involved itself deeply in ordinary people’s dress. The wartime period, and the years that followed, are characterised by government policies such as clothes rationing, the Utility Scheme and the Make-Do and Mend campaign. These sought to control the acquisition and care of clothing, its price, quality and, to some extent, look.

Every citizen was allocated a set number of clothing coupons, a precious commodity in a world where even the simplest garments could be hard to come by. For the first year, it was 66 coupons per person but later reduced to 36. These coupons were used when buying clothing. The number needed for items was preset, in 1941 a woman needed 14 coupons to obtain a coat, 7 for a skirt and 5 for a blouse. A man’s jacket was 13 and a pair of trousers required 8. These coupons became a currency of survival, determining not just what they wore, but how they expressed themselves in a time of uncertainty.

The Utility Scheme

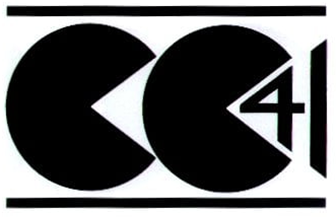

The Board of Trade knew that rationed clothing had to be good quality and created the ‘Utility Scheme’ in 1941. Clothes bore ‘Utility’ labels with a CC41 logo (Civilian Clothing 1941).

These clothes were made using ‘Utility’ cloth which met minimum standards. Prices were controlled and the purchase tax was removed. There were also austerity measures imposed which limited the import of wool, rayon and linen and the materials used for garments. It also banned extra unnecessary aspects such as turn-ups on trousers, additional pockets (no more than 2) and limited buttons to 5. Skirts were allowed only 6 seams and 2–4 pleats depending on whether they were inverted or knife.

There were 32 ‘Utility’ designs created by Hardy Amies and Digby Norton from The Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers. These designs were available to manufacturers for a small fee. Although this scheme officially ended in 1951 it fostered a legacy of minimum standards and increased efficiency in the British manufacture of clothing and textiles.

The second-hand clothing market was important, including hats and make-up, which were not rationed. Despite everything else a woman had to do, looking smart and attractive was considered an important contribution to the war effort in boosting national morale.

You can see the collection catalogue here.

Make Do And Mend

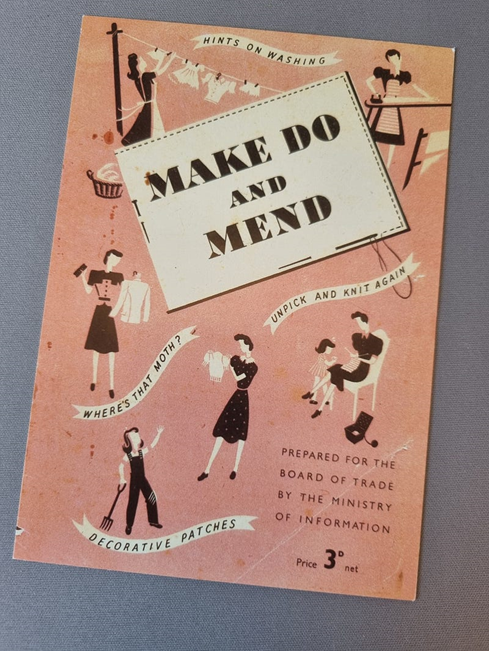

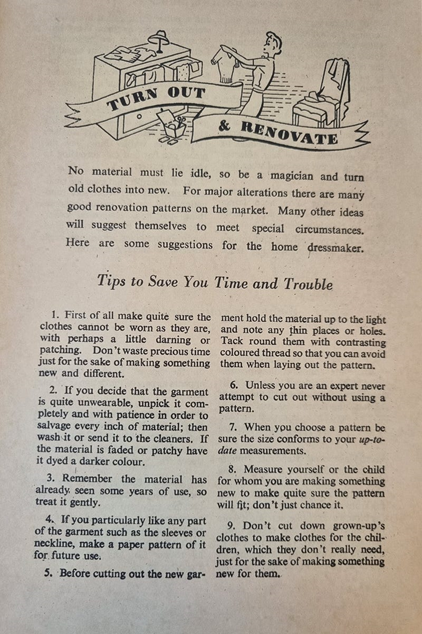

The ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign became a mantra for survival, teaching citizens to cherish every garment, to mend and repurpose with care and ingenuity. What began as a necessity soon became a way of life, shaping not just wardrobes, but attitudes towards consumption and waste.

The ‘Make Do and Mend’ Campaign was publicised with the use of a ‘Mrs Sew and Sew ’ character and pamphlets and booklets produced to enable people to

‘… get the last possible ounce of wear out of all your clothes …’

It covered how to make clothes last longer, how to sew and darn, washing and ironing hints, turning out and renovating and unpicking a garment and knitting again. What has become somewhat of a recycle/reuse trend in the 2000s was a necessity and an expectation in the 1940s.

A friend of mine, who was a child at the time, told me she felt sad for her mother who wouldn’t use her ration for herself but use it to buy fabric to make clothes for her. Her mother was a talented seamstress and on changing schools she created a tailored school blazer in rose pink and a smart buttermilk yellow dress for occasions.

‘Make Do And Mend’ was a necessity, a way of life, and has stayed with my friend throughout her life. Recently she has shared with me her most treasured and beautiful clothes kept, preserved in time, over the many years since, including her first little black dress, her 21st birthday dress and her wedding going away outfit. Her clothes are important to her and have been lovingly cared for. I find this touching and relatable as my mother was also a mother to my brothers and elder sister in the War and often went without to support her children.

Being a Baby Boomer means that much of the ‘Make Do And Mend’ philosophy has been born into me and, I am sure, influences how I feel about my clothes and why I take care of them.

The styles of the 1940s demonstrate an outlet for individuality and creativity. With very little to buy innovation was driven by young women as the prime consumers. Women were employed in the war effort bringing greater earnings and more opportunity to socialise. Young women had newfound independence. Scarcity allowed innovation and many styles still resonate today. Military uniforms and Hollywood films influenced design and innovation which now came from many sources other than French couture.

As the War drew to a close, the legacy of resilience lived on. Scarcity may have defined the era, but creativity shaped its spirit. With the dawn of peace came a renewed sense of hope, a longing for extravagance and luxury in a world that had known only austerity for so long.

Scarcity was still felt and restrictions and shortages carried on long into the second half of the 1940s, clothes rationing did not end until 1949. Indeed rationing food would not cease until the early fifties. Christian Dior’s New Look in 1947 re-asserted the traditional fashion scene bringing with it a relief from hardship and a burst of extravagence.

In the end, the fashion of the 1940s was more than just clothing — it was a symbol of resilience, a testament to the human spirit in the face of adversity. And though the war may have ended, its legacy lives on in every stitch, reminding us that even in our darkest hour, style is a statement of strength, and fashion can be a form of defiance.